Music by Igor Stravinsky, N.Rimsky-Korsakov, A.Glazunov, J. Massenet, M.Ravel, G.Faure, O.F. Tekbilek

From a concept by Andris Liepa

Choreography and staging by Patrick de Bana

Drama by Jean-François Vazelle

Scenery by Pavel Kaplevich

Costumes by Ekaterina Kotova

Concerning Cleopatra

At the turn of the twentieth century, Parisian ballet was an art form without devotees, an outdated amusement at most, , and all too often an excuse to look at young, lightly-clad girls.

It was into this critical atnmosphere that the Saisons Russes burst.

An astute impresario, Diaghilev declared that “A true ballet must consist of the perfect combination of these three elements: music, choreography and decorative painting”.

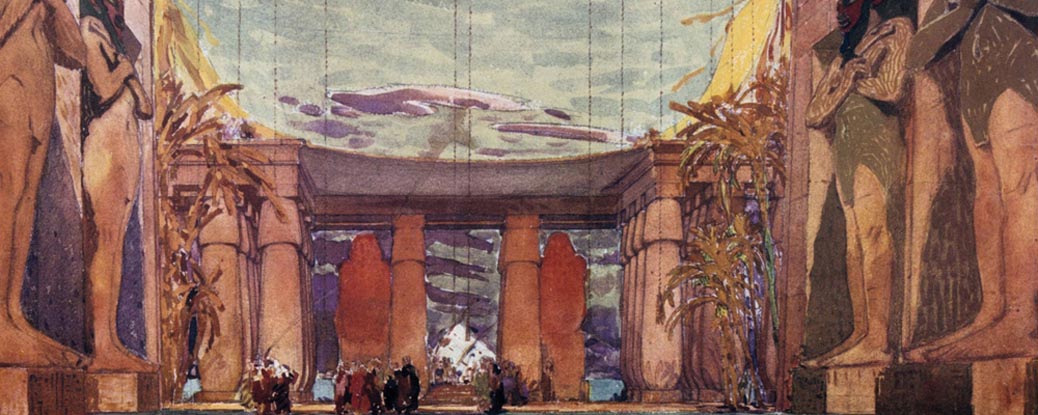

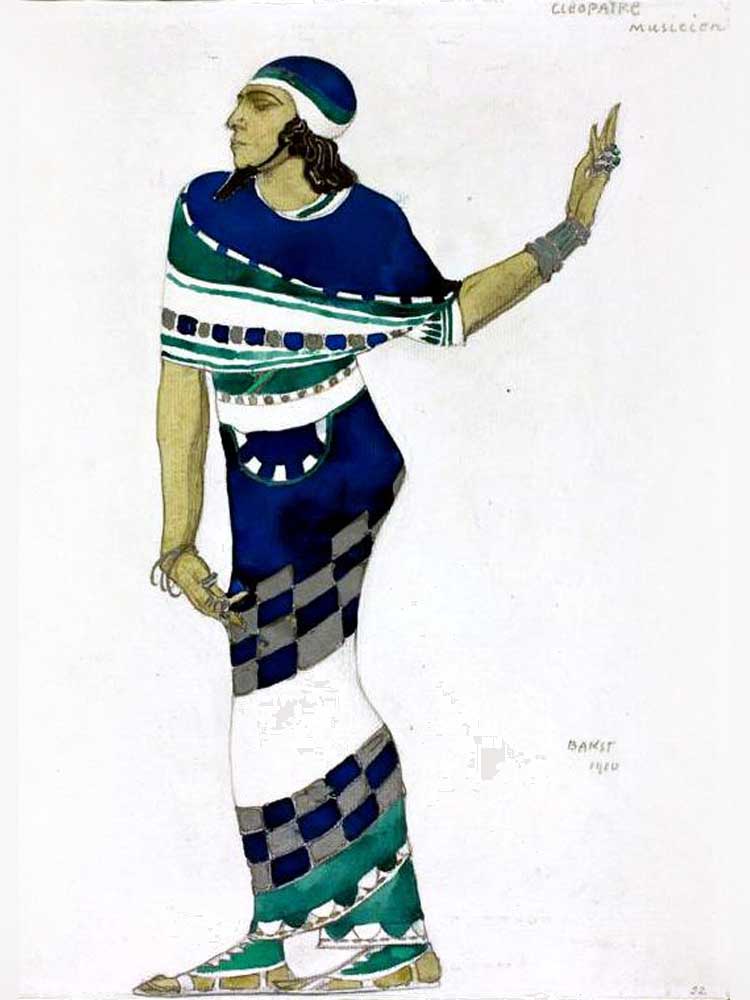

More than a choreographic creation, Cleopatra would be the first act in a revival of spectacle as a central pillar of the ballet, a social and fashionable phenomenon without precedent.

On the evening of 2 June 1909, Paris was given a production the like of which it had never seen.

A breathtaking set by Léon Bakst, dances of an eroticism previously unknown in France, and the dazzling emergence of Ida Rubinstein.

Let us read Count Montesquiou:

“The lady is naked beneath veils studded with precious stones… Barely veiled by a negligée as extravagant as it is transparent,… she entwines her lithe body, like a serpent of the Nile, with the muscular one of Amoun–Fokine in a dance of love; the auditorium is stunned”.

The curtain barely down, he rushes into Ida’s dressing room. Robert de Montesquiou is spellbound, he will put all Paris at her feet…

The following year it was Scheherazade, and even if familiarity with the ballet was limited, sartorial and decorative fashion were transformed, and Parisian life turned upside-down: at Paul Poiret, the women clamoured for Scheherazade lamé turbans, gowns embellished with gemstones and fur, and a night-club bearing the name opened on the Rue de Liège…

Ida Rubinstein became the icon of artistic Paris, of pre-war Paris, the world- and cosmopolitan capital of artistic Creation. She became the ambassador of “Total Art”.

Rubinstein was an extraordinary woman: fabulously wealthy by birth and unimpeachably cultivated, Ida was not a dancer; but she was beautiful, she possessed the art of graceful movement, and she was hungry for theatrical success. She dreamed of competing with Diaghilev, and stealing from him the adoration of the Parisian public.She would place her fortune (and that of her lover, the Irish magnate Walter Guinness) at the service of that ambition.

She would place her fortune (and that of her lover, the Irish magnate Walter Guinness) at the service of her ambition.

In Robert de Montesquieu-Fézensac she found a guide, an intermediary of genius through whom she met everyone who was anyone in Paris. There was the Italian Modernist poet and sage Gabriele d’Annunzio (whow as, of course, madly in love with Ida); there were Débussy, Ravel (whose Boléro she inspired), Sarah Bernhardt (who would give her acting lessons); there were Honegger, Milhaud, Cocteau, Claudel, Stravinsky… and many, many more!

Ida tirelessly pursued her career as producer, company manager, and of course as performer until 1939. But she modern woman also funded hospitals during both World Wars, and actively championed the Jewish cause even though she herself became a Catholic mystic.

Beyond Mikhail Fokine’s ballet, it is this destiny, this life which we hope to evoke through the individual prism of Ida Rubinstein. To recall this premiere and its success. To follow Ida through the ebb and flow of her thoughts, her joys, her fears, and her uncertainties as she prepares to portray the divine Egyptian.

A series of snapshots in which she recalls intense moments in her life, and the individuals who are dear to her.

Jean-François Vazelle